Imagine that you work for a federal agency like the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) or Department of Homeland Security (DHS) or National Security Agency (NSA) and receive intelligence suggesting that Russia or Iran was crafting some kind of meme campaign aimed at disrupting U.S. elections. How should the Intelligence Community (IC) respond?

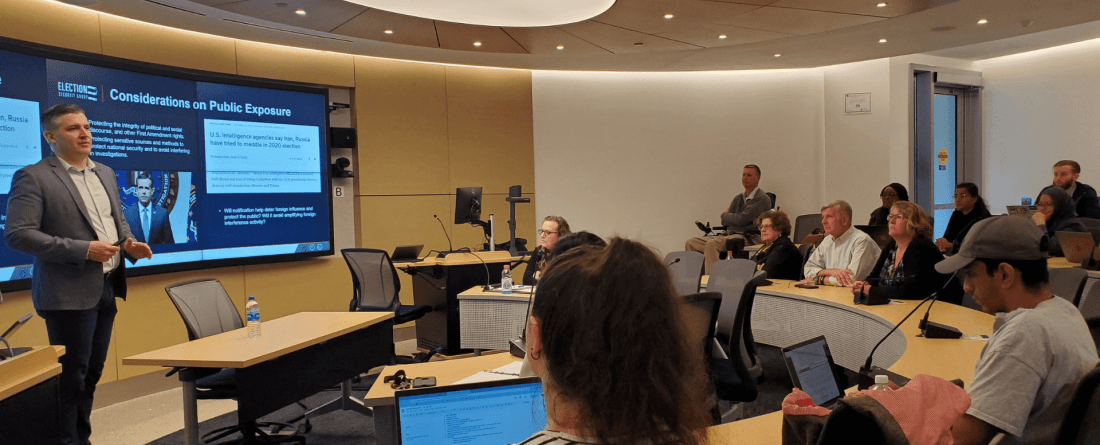

This was the question that David Imbordino, a senior executive and former 2020 election security lead at the NSA, posed to audience members during his recent visit to the UMD School of Public Policy and the Center for Governance of Technology and Systems (GoTech).

“The decisions aren’t always clear cut,” Imbordino explained. In fact, the suite of potential responses is vast, ranging from doing nothing and allowing the campaign to play itself out on one end of the spectrum to advocating for a kinetic strike on the other end.

Imbordino's talk offered the SPP community a glimpse into how the IC safeguards U.S. elections from foreign threats and provided some context around the types of decisions IC professionals must make in carrying out their mission. The event was the latest installment in GoTech’s Expert Lecture Series.

“Elections are fundamentally human systems supported by technology, and whose complexities are often at the center of governance challenges for public officials,” said Charles Harry, director of GoTech. “GoTech is building a larger community of researchers and practitioners to explore the intersections between human and technical systems and our expert lecture series gives us the opportunity to explore specific examples of how the government can respond in a larger and holistic manner. “

Imbordino, who originally hails from the Chicago area, has been with the NSA for over two decades, including six years in counterterrorism and three years in cybersecurity. Election security became especially pressing in the wake of the 2016 election, when the Internet Research Agency, a Russia-based disinformation operation, attempted to influence the outcome of the presidential race. 2016 was also the year when operatives connected to the Russian GRU managed to hack Democratic officials affiliated with the Clinton campaign, using a “spear phishing” technique to steal and leak internal documents. After the much-publicized foreign interference attempts in 2016, the pressure was on the IC to mitigate any threats in the contentious 2020 election.

“That’s why I got all this gray hair,” quipped Imbordino.

While the nuts and bolts of running elections and tabulating votes is mostly done at the local and state levels, the federal IC plays a major role in managing election security. But ensuring security across 50 states and their voting districts is easier said than done.

”It’s very fragmented,” said Imbordino. “So how do you scale security in a scenario like that?”

The IC, which includes the NSA working in tandem with agencies like the FBI and DHS among many others, manages election security several ways. They investigate and uncover adversary activities, counter interference attempts, and keep policymakers and other stakeholders informed. In 2020, for instance, the IC routinely briefed both presidential campaigns on foreign interference attempts.

Each agency also takes on more specialized tasks. For instance, DHS interfaces directly with state and local governments, while the FBI’s Foreign Influence Task Force communicates with social media companies on instances of misinformation and disinformation that may violate terms of service agreements.

Imbordino described the NSA’s role in 2020 as working “across government and industry to detect, defend against, deter and disrupt foreign interference and malign influence to ensure a safe and secure…election.” He went on to outline several frequent adversaries' preferred “styles” of election interference, including Iran’s penchant for the spear phishing technique and China’s “broad scale cyber operations to compromise intellectual property, private networks and private citizen data.”

In terms of information campaigns, “(there was a) general desire to sow discord in the U.S.,” said Imbordino. “Gun rights, abortion rights, racial issues…They would sit there and take both sides and amplify both narratives just to try to get the general populace of the U.S. to be more angry with each other.”

Imbordino also described a technique attempted by Iran in 2020 called “perception hacking.” In a perception hack, an adversary doesn’t need to successfully execute a hack to spark chaos-they just need to proliferate the idea that a hack has been successful to cause structural damage to Americans’ trust in election results.

In response to this broad range of threats, the IC has started to rely more on a response that might seem surprising coming from agencies often associated with secrecy: sharing intelligence with the public. Sometimes, according to Imbordino, “sunlight is the best disinfectant.” Other times, the IC still opts to play things closer to the chest.

”Generally the IC and others are not fans of ‘let’s just put that out there,’” Imbordino said. “If you’re jumping around waving your hands in public, you’re doing the adversaries’ job… so it comes down to whether you are getting the right message to a broader audience than it would have reached otherwise?”

After the talk, Imbordino took a series of questions, many of which concerned job opportunities at the NSA. Imbordino described working in election security as an area of government where everyone is “pulling in the same direction.”

Although Imbordino acknowledged that the NSA hires a lot of STEM students, there are also opportunities in intelligence analysis for people with international affairs degrees. He noted that the hiring process at NSA is lengthy, often lasting up to 18 months, and encouraged anyone interested to start the process of trying to apply for a job sooner rather than later.